Strange are the Ways of Cement and Concrete

Dr. Anil K Kar, Engineering Services International, Kolkata; Arun Kumar Chakraborty, Asst. Professor,Civil Engineering and A K Sarkar, Civil Engineering Bengal. Engineering, and Science University, Shibpur

It is commonly known that the rate of gain in strength in the initial period is faster in the case of ordinary portland cement (OPC) than in the cases of portland slag cement (PSC) and Portland pozzolana or flyash cement (PPC). It is generally... observed that after the first few weeks of moist curing, further gain in strength in the case of OPC concrete is insignificant (lower curve in Figure 1), whereas concrete with blended cement (PSC and PPC) can gain considerable strength beyond the first week or two of concreting (Figure 2).

Much of the knowledge, more particularly impression, about concrete and concrete structures is based on the performance of well cured concrete and concrete structures which were built decades ago with OPC of that time. The impressions, many a people have about concrete, is that concrete is impervious and naturally waterproof. Another impression, people carry from the past, is that concrete structures are durable.

Much of the knowledge, more particularly impression, about concrete and concrete structures is based on the performance of well cured concrete and concrete structures which were built decades ago with OPC of that time. The impressions, many a people have about concrete, is that concrete is impervious and naturally waterproof. Another impression, people carry from the past, is that concrete structures are durable.

Much has changed over the years with cement and construction practices, hastening the decay and distress in modern concrete structures.

This paper is an attempt to study the changed ways of cement and concrete. This is limited to studying the influence of the duration of moist curing on the compressive strength of concrete with OPC, PSC, and PPC.

Though blended cements find a very considerable share of the construction market in India today, the earlier practice was to use mostly OPC.

It was an old practice in the era of OPC to provide 28 days' moist curing to concrete.

Over the years, OPC went through many modifications in its chemical compositions and physical characteristics, resulting in higher ultimate strength and the development of most of this ultimate strength within a week or two of concreting (lower curve in Figure 1).

This early attainment of much of the ultimate strength and a greater emphasis on early completion of projects made the codes/standards lower the required period of moist curing. The Indian Standard Code of Practice for Plain and Reinforced Concrete, IS:456:20001, as well as its earlier version2 lowered the requirement of the minimum period of moist curing of OPC concrete from 28 days in earlier decades to 7 days.

Increasingly, cement manufacturers in India started marketing blended cements aggressively. Because of slower rates of hydration, it became necessary to set standards at longer periods of moist curing of concrete with blended cements.

In order that concrete of comparable mix proportions with blended cements may yield comparable or higher (than 28-day OPC concrete strength) strengths, researchers generally recommend 56 to 90 days of moist curing of concrete in the case of blended cements with mineral admixtures. The Indian code1, however, considers it sufficient to cure such concrete with blended cements for only 10 days. The code recommends that this minimum period of 10 days may be extended to 14 days. The earlier code required 7 days' moist curing for concrete with blended cements too.

Though the code1 considers moist curing for periods ranging between 7 to 10 days to be adequate for concrete construction with different types of cement and though the duration of effective curing of concrete during construction may be even less thanthe periods specified in the code 1 , the design and construction of concrete structures are based on compressive strength of well compacted concrete samples after 28 days of moist curing.

Besides the shortcomings, which may arise as a result of the gap between the required (considered desirable by researchers on the basis of attainment of strength) and mandated (by the code) periods of moist curing, and besides the obvious gap between the design (tested after 28 days' moist curing) and the actual periods of curing, Kar3-7 has pointed out that today's cement is in many ways different from cements which were used till a few decades ago and which had given durable concrete structures. Furthermore, Kar3-7 has shown that today's cement in India may contain harmful alkalis to make concrete less durable or even self-destructive (curve for PPC in Figure 2).

In this scenario, it is considered appropriate: (a) to study the influence of curing on the development of strength in concrete and (b) to examine the reasonableness of the codal provisions on the duration of moist curing of concrete. This is done for concrete, made with the three basic types of cement (viz., OPC, PSC and PPC).

" The code1 also requires that "Exposed surfaces of concrete shall be kept continuously in a damp or moist condition by ponding or by covering with a layer of sacking, canvas, hessian or similar materials and kept constantly moist for at least seven days from the date of placing concrete in case of ordinary Portland Cement and at least 10 days where mineral admixtures or blended cements are used. The period of curing shall not be less than 10 days for concrete exposed to dry and hot weather conditions. In the case of concrete where mineral admixtures or blended cements are used, it is recommended that above minimum periods may by extended to 14 days."

It appears from the language of the code that the extension of the curing period from 10 days to 14 days is not mandatory.

It is of interest to note here that the provisions in IS :456-20001 were considered reasonable eight years ago, whereas the provisions in IS :456-19782, which permitted 7 days' moist curing for concrete with OPC, PPC as well as PSC, were considered reasonable at least thirty years ago.

During the intervening 22 years between the two codes, many structures with PSC concrete must have been cured moist for 7 days or less.

During the intervening period between the two codes1.2 and during the period following the more recent code, cement has undergone very significant changes in chemical compositions and physical characteristics3-7.

The resulting effects of such changes include the generation of considerable heat inside concrete at early ages. There is also the exothermic reaction from the high contents of water soluble alkalis in Indian cement of today3-7, further hastening the rate of hydration of cement, thereby leading to still faster gain in strength. All of these can make it possible to lower the required period of moist curing if the attainment of strength in concrete will become the only criterion in the determination of the adequacy of any particular period of moist curing of concrete. This would suggest that even if it may be found that today's high early strength cements may yield strengths within acceptable ranges on satisfaction of the requirements of the mandated moist curing for short periods, such short duration curing in the past might not have yielded concrete strengths close to the design strengths at 28 days.

As stated earlier, it is studied here whether the stipulated periods of moist curing, set in IS:456-2000 1 for concrete with OPC and blended cements, are reasonable or not. This is done with cement that is available in the Kolkata region today. The tests for compressive strength were conducted using 150 mm cubes with cements of several nationally and internationally known brands.

The evaluation of the adequacy of the period of curing is made from the consideration of attainment of strength as a percentage of strength at 28 days of moist curing.

It is well–known that moist curing, particularly at the initial periods, reduces the permeability of concrete. It is further known that greater the impermeability, better is likely to be the durability of concrete structures. In clause 8, the code 1 has, however, given four options for lengthening the life of concrete structures. Kar8 has explained that among the four options, given in the code, only the option of providing surface coatings/protection systems to concrete structures is practical in lengthening the life of concrete structures.

Since the provision of surface protection systems will effectively make concrete surfaces or structures impervious to the external agents of decay, any shortcomings in the form of greater permeability of concrete due to any inadequacy in curing loses some or much of any significance. Accordingly, no serious attempt is made to study the effects of curing on the permeability of concrete at 7 or 10 days vis-a-vis permeability of concrete cured moist for 28 days.

There may be additional tests for setting times for workability and expansion as an yardstick for durability.

Five sets of curves are presented here as a part of the study on the influence of the period of moist curing on concrete strength.

Figure 1 shows the compressive strength of OPC concrete. The lower curve in Figure 1 represents the strength of OPC on the completion of moist curing for 1, 3, 7, 10, 14, 21 and 28 days as is the conventional practice. In this particular case, the 7-day strength of 26.22 MPa is 77.6% of the 28-day strength of 33.78 MPa.

It would appear that the mandated curing period (minimum) of 7 days may or may not lead to an endangerment of the safety of an OPC concrete structure if it would have been designed and constructed in accordance with the 28-day strength but cured moist for 7 days and loaded immediately thereafter. The real situation is better if the structure will not be loaded immediately after 7 days of moist curing, as explained below.

An interesting observation can be made here with the help of the upper curve in Figure 1 which represents the compressive strength of the concrete as that in the lower curve, except that the upper curve represents the compressive strengths at 28 days for cube samples which were cured moist for different periods from 0 to 28 days. It is observed that the peak concrete strength of 37.90 MPa at 28 days is higher than the concrete strength of 33.78 MPa when it is cured moist for a period less than 28 days. In this particular case, it so happens that the peak strength at 28 days is available when concrete is cured moist for 7 days, and then cured in air a further period of 21 days. In the same token, it is observed that in the event the concrete in Figure 1 would not be cured moist at all, but kept covered or in shade, a minimum strength of 30.46 MPa would develop at 28 days, which is 90% of the strength of the concrete, if it would be cured moist for 28 days. This is not too bad a situation where concrete may not be moist cured at all and the attainment of strength of concrete will be the only consideration.

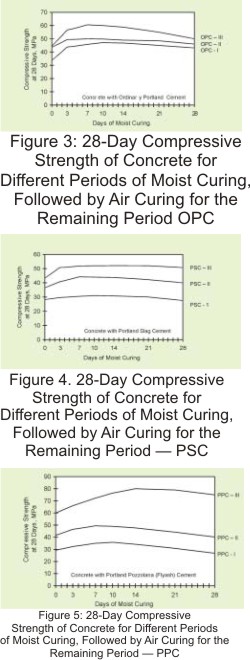

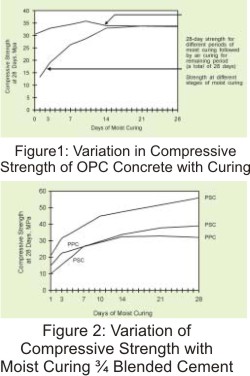

Figure 2 shows the gain in compressive strength of PPC concrete from one batch and PSC concrete from two batches. The 150 mm cubes were cured moist for different durations. The cubes were tested for compressive strength at the end of each period of curing. The samples were cast in the month of April 2008. It is noticed that the compressive strength of concrete at the end of stipulated 1 periods (10 days) of moist curing is 76 to 80 percent of the 28-day strength in the case of PSC concrete whereas it is 91 percent in the case of PPC concrete.

Since structural elements e.g., floor slabs and floor beams are frequently loaded close to their design loads during construction stages, it is recognized here that it may not be unreasonable if the moist curing will be terminated at the end of 10 days in the case of PPC concrete, but the same cannot be said in the case of PSC concrete. It will be seen later that if loading of the structure will be delayed, moist curing of the structure or structural element for 10 days may not be too unreasonable.

It is recalled here that the code1 permits 7 days' moist curing in the case of OPC concrete and 10 days' moist curing in the case of concrete with blended cements, whereas (a) the design is based on compressive strength after moist curing for 28 days, and (b) real structures are seldom cured moist for the stipulated (in the code) periods.

In consideration of the above, it would appear that if adequate care will not be taken to limit construction or service loads, immediately upon the termination of moist curing, to within 70% of the design loads, and that too with appropriate margins for various uncertainties, the stipulated periods of curing will prove to be unreasonable. It is seen in the following that the picture is not necessarily unreasonable, if

In contention of the above, three cases are studied in the following. These include cases:

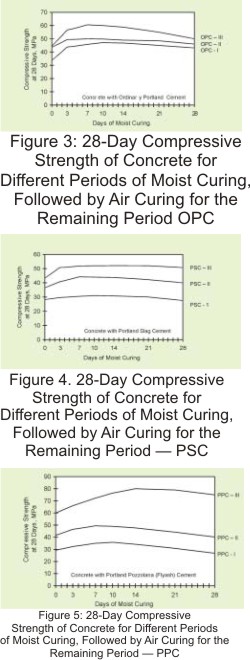

It is seen in each case in Figures 3 to 5 that the peak compressive strength is recorded when concrete is tested at 28 days but the moist curing is between 3 to 14 days (Tables 1 – 3).

Among all the three batches of OPC concrete (Table 1), it is seen that strengths equal to or higher than the strengths, at 28 days' moist curing, can be obtained if the moist curing will be discontinued after 3 days.

It is further noticed in Figure 3 and Table 1 that in two cases the peak strengths in OPC concrete were obtained when concrete was cured moist for 7 days, followed by air curing for 21 days before the test. In fact, the 28-day (moist curing) compressive strength was lower than the peak strength (at 7- day moist curing followed by 21 days' air curing) by as much as 17.4 percent in one case.

In the case of PSC concrete (Figure 4 and Table 2), the peak strengths were gained when concrete was cured moist for 7 to 14 days, followed by air curing for the remaining days. In the three cases of PSC too, it is seen that the 28-day strength could be reached by discontinuing moist curing after 3 days. It's noticed that with continued moist curing, there is a drop of strength (from the peak) by as much as 11.3 percent.

In the case of PPC concrete (Figure 5, Table 3), the peak strengths were obtained after 7 to 14 days' moist curing, followed by air curing till 28 days from concreting. In two of the cases, the strengths of concrete were higher than the 28-day strengths when the cubes were cured moist for 3 days, followed by curing in air for 25 days. In the remaining case (Case III), the 28-day strength (moist cured) could be obtained with 9 days' moist curing, followed by 19 days of air curing. In case I (Table 3), there is a drop of 25.1 percent in the peak strength with continued moist curing beyond 10 days.

It is seen that the stipulated1 period of 7 days' moist curing in the case of OPC and 10 days in the case of blended cements is justified as far as matching the 28- day (moist cured) strength is concerned provided that the structures will not be loaded till 28 days after concreting.

It is seen that the stipulated2 period of 7 days' moist curing for concrete with blended cements, as in Ref. 2, was not reasonable, particularly when cement of the earlier periods did not gain strength as early as it does today.

From the performance of four batches of OPC concrete (1 in Figure 1 and 3 in Figure 3), it appears that curing concrete, with today's OPC, for 3 days in moist condition will be sufficient if matching the 28-day design strength will be the only criterion and the structures will not be loaded until 28 days after concreting.

From the performance of nine batches of PPC and PSC concrete (3 each in Figures. 2,4 and 5), it appears that except in one case of PPC concrete, curing concrete, with today's PPC and PSC, for 3 days in moist condition will be sufficient if matching the 28-day design strength will be the only criterion to be fulfilled and the structures will not be loaded until 28 days after concreting. In case III of PPC in Figure 5, moist curing of 9 days, followed by air curing of 19 days, leads to a matching of compressive strength of concrete if such concrete will be cured moist for 28 days before loading.

A closer study of the various curves in Figures 1 to 5 show a decreasing trend for the strength of concrete with continued moist curing after the peak strength will have been reached much earlier than 28 days. This challenges the widely held concept about concrete that concrete increases in strength with continued curing in moist condition.

Studies are underway to determine if the declining strength with increasing moist curing has more to do with impurities in today's cement3-7 or with any lingering damp/ moist condition of the test samples after the initial period of moist curing.

Introduction

It is commonly recognized that the compressive strength and other useful properties of concrete increase with increasing duration of curing, more particularly moist curing (lower curve in Figure 1). This knowledge of increasing compressive strength with increasing periods of moist curing has been gained from tests over the years where standard cubes or cylinders of concrete are tested on the last day or a day after a specified period of moist curing.It is commonly known that the rate of gain in strength in the initial period is faster in the case of ordinary portland cement (OPC) than in the cases of portland slag cement (PSC) and Portland pozzolana or flyash cement (PPC). It is generally... observed that after the first few weeks of moist curing, further gain in strength in the case of OPC concrete is insignificant (lower curve in Figure 1), whereas concrete with blended cement (PSC and PPC) can gain considerable strength beyond the first week or two of concreting (Figure 2).

Much has changed over the years with cement and construction practices, hastening the decay and distress in modern concrete structures.

This paper is an attempt to study the changed ways of cement and concrete. This is limited to studying the influence of the duration of moist curing on the compressive strength of concrete with OPC, PSC, and PPC.

Though blended cements find a very considerable share of the construction market in India today, the earlier practice was to use mostly OPC.

It was an old practice in the era of OPC to provide 28 days' moist curing to concrete.

Over the years, OPC went through many modifications in its chemical compositions and physical characteristics, resulting in higher ultimate strength and the development of most of this ultimate strength within a week or two of concreting (lower curve in Figure 1).

This early attainment of much of the ultimate strength and a greater emphasis on early completion of projects made the codes/standards lower the required period of moist curing. The Indian Standard Code of Practice for Plain and Reinforced Concrete, IS:456:20001, as well as its earlier version2 lowered the requirement of the minimum period of moist curing of OPC concrete from 28 days in earlier decades to 7 days.

Increasingly, cement manufacturers in India started marketing blended cements aggressively. Because of slower rates of hydration, it became necessary to set standards at longer periods of moist curing of concrete with blended cements.

In order that concrete of comparable mix proportions with blended cements may yield comparable or higher (than 28-day OPC concrete strength) strengths, researchers generally recommend 56 to 90 days of moist curing of concrete in the case of blended cements with mineral admixtures. The Indian code1, however, considers it sufficient to cure such concrete with blended cements for only 10 days. The code recommends that this minimum period of 10 days may be extended to 14 days. The earlier code required 7 days' moist curing for concrete with blended cements too.

Though the code1 considers moist curing for periods ranging between 7 to 10 days to be adequate for concrete construction with different types of cement and though the duration of effective curing of concrete during construction may be even less thanthe periods specified in the code 1 , the design and construction of concrete structures are based on compressive strength of well compacted concrete samples after 28 days of moist curing.

Besides the shortcomings, which may arise as a result of the gap between the required (considered desirable by researchers on the basis of attainment of strength) and mandated (by the code) periods of moist curing, and besides the obvious gap between the design (tested after 28 days' moist curing) and the actual periods of curing, Kar3-7 has pointed out that today's cement is in many ways different from cements which were used till a few decades ago and which had given durable concrete structures. Furthermore, Kar3-7 has shown that today's cement in India may contain harmful alkalis to make concrete less durable or even self-destructive (curve for PPC in Figure 2).

In this scenario, it is considered appropriate: (a) to study the influence of curing on the development of strength in concrete and (b) to examine the reasonableness of the codal provisions on the duration of moist curing of concrete. This is done for concrete, made with the three basic types of cement (viz., OPC, PSC and PPC).

Codal Provisions on Curing

Among the different provisions on curing of concrete, IS:456-20001 suggests that "Curing is the process of preventing the loss of moisture from the concrete whilst maintaining a satisfactory temperature regime. The prevention of moisture loss from the concrete is particularly important if the watercement ratio is low, if the cement has a high rate of strength development, if the concrete contains granulated blast furnace slag or pulverised fuel ash. The curing regime should also prevent the development of high temperature gradients within the concrete." The code1 also requires that "Exposed surfaces of concrete shall be kept continuously in a damp or moist condition by ponding or by covering with a layer of sacking, canvas, hessian or similar materials and kept constantly moist for at least seven days from the date of placing concrete in case of ordinary Portland Cement and at least 10 days where mineral admixtures or blended cements are used. The period of curing shall not be less than 10 days for concrete exposed to dry and hot weather conditions. In the case of concrete where mineral admixtures or blended cements are used, it is recommended that above minimum periods may by extended to 14 days."

It appears from the language of the code that the extension of the curing period from 10 days to 14 days is not mandatory.

It is of interest to note here that the provisions in IS :456-20001 were considered reasonable eight years ago, whereas the provisions in IS :456-19782, which permitted 7 days' moist curing for concrete with OPC, PPC as well as PSC, were considered reasonable at least thirty years ago.

During the intervening 22 years between the two codes, many structures with PSC concrete must have been cured moist for 7 days or less.

During the intervening period between the two codes1.2 and during the period following the more recent code, cement has undergone very significant changes in chemical compositions and physical characteristics3-7.

The resulting effects of such changes include the generation of considerable heat inside concrete at early ages. There is also the exothermic reaction from the high contents of water soluble alkalis in Indian cement of today3-7, further hastening the rate of hydration of cement, thereby leading to still faster gain in strength. All of these can make it possible to lower the required period of moist curing if the attainment of strength in concrete will become the only criterion in the determination of the adequacy of any particular period of moist curing of concrete. This would suggest that even if it may be found that today's high early strength cements may yield strengths within acceptable ranges on satisfaction of the requirements of the mandated moist curing for short periods, such short duration curing in the past might not have yielded concrete strengths close to the design strengths at 28 days.

As stated earlier, it is studied here whether the stipulated periods of moist curing, set in IS:456-2000 1 for concrete with OPC and blended cements, are reasonable or not. This is done with cement that is available in the Kolkata region today. The tests for compressive strength were conducted using 150 mm cubes with cements of several nationally and internationally known brands.

The evaluation of the adequacy of the period of curing is made from the consideration of attainment of strength as a percentage of strength at 28 days of moist curing.

It is well–known that moist curing, particularly at the initial periods, reduces the permeability of concrete. It is further known that greater the impermeability, better is likely to be the durability of concrete structures. In clause 8, the code 1 has, however, given four options for lengthening the life of concrete structures. Kar8 has explained that among the four options, given in the code, only the option of providing surface coatings/protection systems to concrete structures is practical in lengthening the life of concrete structures.

Since the provision of surface protection systems will effectively make concrete surfaces or structures impervious to the external agents of decay, any shortcomings in the form of greater permeability of concrete due to any inadequacy in curing loses some or much of any significance. Accordingly, no serious attempt is made to study the effects of curing on the permeability of concrete at 7 or 10 days vis-a-vis permeability of concrete cured moist for 28 days.

Codal Provisions and Effects of Curing

It is a common practice, in the acceptance of cement and concrete, to ensure that concrete has the required compressive strength.There may be additional tests for setting times for workability and expansion as an yardstick for durability.

Five sets of curves are presented here as a part of the study on the influence of the period of moist curing on concrete strength.

Figure 1 shows the compressive strength of OPC concrete. The lower curve in Figure 1 represents the strength of OPC on the completion of moist curing for 1, 3, 7, 10, 14, 21 and 28 days as is the conventional practice. In this particular case, the 7-day strength of 26.22 MPa is 77.6% of the 28-day strength of 33.78 MPa.

It would appear that the mandated curing period (minimum) of 7 days may or may not lead to an endangerment of the safety of an OPC concrete structure if it would have been designed and constructed in accordance with the 28-day strength but cured moist for 7 days and loaded immediately thereafter. The real situation is better if the structure will not be loaded immediately after 7 days of moist curing, as explained below.

An interesting observation can be made here with the help of the upper curve in Figure 1 which represents the compressive strength of the concrete as that in the lower curve, except that the upper curve represents the compressive strengths at 28 days for cube samples which were cured moist for different periods from 0 to 28 days. It is observed that the peak concrete strength of 37.90 MPa at 28 days is higher than the concrete strength of 33.78 MPa when it is cured moist for a period less than 28 days. In this particular case, it so happens that the peak strength at 28 days is available when concrete is cured moist for 7 days, and then cured in air a further period of 21 days. In the same token, it is observed that in the event the concrete in Figure 1 would not be cured moist at all, but kept covered or in shade, a minimum strength of 30.46 MPa would develop at 28 days, which is 90% of the strength of the concrete, if it would be cured moist for 28 days. This is not too bad a situation where concrete may not be moist cured at all and the attainment of strength of concrete will be the only consideration.

Figure 2 shows the gain in compressive strength of PPC concrete from one batch and PSC concrete from two batches. The 150 mm cubes were cured moist for different durations. The cubes were tested for compressive strength at the end of each period of curing. The samples were cast in the month of April 2008. It is noticed that the compressive strength of concrete at the end of stipulated 1 periods (10 days) of moist curing is 76 to 80 percent of the 28-day strength in the case of PSC concrete whereas it is 91 percent in the case of PPC concrete.

Since structural elements e.g., floor slabs and floor beams are frequently loaded close to their design loads during construction stages, it is recognized here that it may not be unreasonable if the moist curing will be terminated at the end of 10 days in the case of PPC concrete, but the same cannot be said in the case of PSC concrete. It will be seen later that if loading of the structure will be delayed, moist curing of the structure or structural element for 10 days may not be too unreasonable.

It is recalled here that the code1 permits 7 days' moist curing in the case of OPC concrete and 10 days' moist curing in the case of concrete with blended cements, whereas (a) the design is based on compressive strength after moist curing for 28 days, and (b) real structures are seldom cured moist for the stipulated (in the code) periods.

In consideration of the above, it would appear that if adequate care will not be taken to limit construction or service loads, immediately upon the termination of moist curing, to within 70% of the design loads, and that too with appropriate margins for various uncertainties, the stipulated periods of curing will prove to be unreasonable. It is seen in the following that the picture is not necessarily unreasonable, if

- concrete will be cured moist for at least 3 days, and

- the structure will not be loaded until 28 days after concreting or some such days after concreting as may be determined from tests for particular batches of cement.

In contention of the above, three cases are studied in the following. These include cases:

- When the design is based on compressive strength of concrete after 28 days' moist curing but the concrete is cured for the stipulated period of 7 or 10 days and the structural element is not loaded until 28 days.

- The concrete is cured for 3 days and the structural element is not loaded until 28 days.

- Where the design is based on compressive strengths of concrete after 28 days' moist curing but the concrete is not provided with any moist curing and the structural element is not loaded until 28 days.

It is seen in each case in Figures 3 to 5 that the peak compressive strength is recorded when concrete is tested at 28 days but the moist curing is between 3 to 14 days (Tables 1 – 3).

Among all the three batches of OPC concrete (Table 1), it is seen that strengths equal to or higher than the strengths, at 28 days' moist curing, can be obtained if the moist curing will be discontinued after 3 days.

It is further noticed in Figure 3 and Table 1 that in two cases the peak strengths in OPC concrete were obtained when concrete was cured moist for 7 days, followed by air curing for 21 days before the test. In fact, the 28-day (moist curing) compressive strength was lower than the peak strength (at 7- day moist curing followed by 21 days' air curing) by as much as 17.4 percent in one case.

In the case of PSC concrete (Figure 4 and Table 2), the peak strengths were gained when concrete was cured moist for 7 to 14 days, followed by air curing for the remaining days. In the three cases of PSC too, it is seen that the 28-day strength could be reached by discontinuing moist curing after 3 days. It's noticed that with continued moist curing, there is a drop of strength (from the peak) by as much as 11.3 percent.

In the case of PPC concrete (Figure 5, Table 3), the peak strengths were obtained after 7 to 14 days' moist curing, followed by air curing till 28 days from concreting. In two of the cases, the strengths of concrete were higher than the 28-day strengths when the cubes were cured moist for 3 days, followed by curing in air for 25 days. In the remaining case (Case III), the 28-day strength (moist cured) could be obtained with 9 days' moist curing, followed by 19 days of air curing. In case I (Table 3), there is a drop of 25.1 percent in the peak strength with continued moist curing beyond 10 days.

It is seen that the stipulated1 period of 7 days' moist curing in the case of OPC and 10 days in the case of blended cements is justified as far as matching the 28- day (moist cured) strength is concerned provided that the structures will not be loaded till 28 days after concreting.

It is seen that the stipulated2 period of 7 days' moist curing for concrete with blended cements, as in Ref. 2, was not reasonable, particularly when cement of the earlier periods did not gain strength as early as it does today.

Concluding Remarks

There is an increasing trend to shorten the period of moist curing of concrete. The Indian code IS:456- 20001 has lowered the required period of moist curing of concrete to 7 days in the case of OPC and 10 days in the case of blended cements with mineral admixtures. The period of 10 days is, however, higher than what was specified in Ref. 2. In some countries, the minimum period of moist curing has been lowered to 3 days and in real cases in India many concrete structures are not provided any moist curing.From the performance of four batches of OPC concrete (1 in Figure 1 and 3 in Figure 3), it appears that curing concrete, with today's OPC, for 3 days in moist condition will be sufficient if matching the 28-day design strength will be the only criterion and the structures will not be loaded until 28 days after concreting.

From the performance of nine batches of PPC and PSC concrete (3 each in Figures. 2,4 and 5), it appears that except in one case of PPC concrete, curing concrete, with today's PPC and PSC, for 3 days in moist condition will be sufficient if matching the 28-day design strength will be the only criterion to be fulfilled and the structures will not be loaded until 28 days after concreting. In case III of PPC in Figure 5, moist curing of 9 days, followed by air curing of 19 days, leads to a matching of compressive strength of concrete if such concrete will be cured moist for 28 days before loading.

A closer study of the various curves in Figures 1 to 5 show a decreasing trend for the strength of concrete with continued moist curing after the peak strength will have been reached much earlier than 28 days. This challenges the widely held concept about concrete that concrete increases in strength with continued curing in moist condition.

Studies are underway to determine if the declining strength with increasing moist curing has more to do with impurities in today's cement3-7 or with any lingering damp/ moist condition of the test samples after the initial period of moist curing.

References

- IS:456-2000, Indian Standard, Plain and Reinforced Concrete Code of Practice (Fourth Revision), Bureau of Indian Standards, New Delhi, July 2000.

- IS:456-1978, Indian Standard Code of Practice for Plain and Reinforced Concrete, Third Edition, Bureau of Indian Standards, New Delhi, September 1978.

- Kar, A. K., "Concrete Structures We Make Today," New Building Materials & Construction World, New Delhi Vol. 12, Issue 8,February 2007.

- Kar, A. K., "The Ills of Today's Cement and Concrete Structures," Journal of the Indian Roads Congress, Vol. 68, Part 2, July- September 2007.

- Kar, A. K., "Durability of Concrete Bridges and Roadways," New Building Materials & Construction World, New Delhi, Vol. 13, Issue 3, September 2007.

- Kar, A. K., "Woe Betide Today's Concrete Structures," Part I New Building Materials & Construction World, New Delhi, Vol. 13, Issue- 8, February, 2008.

- Kar, A. K., "Woe Betide Today's Concrete Structures," Part II New Building Materials & Construction World, New Delhi, Vol.13, Issue- 9, March, 2008.

- Kar, A. K., "IS 456:2000 On Durable Concrete Structures," New Building Materials & Construction World, New Delhi, Vol. 9, Issue-6, December, 2003.s

NBM&CW July 2008