Carlo Scarpa the Visionary

Carlo Scarpa was an Italian designer with a profound understanding of materials, landscape, and the history of Venetian culture, particularly its tradition of painting. He belongs to the generation of Italian architects working in a period when political conditions placed severe restrictions on architectural expression. Scarpa’s achievements surpassed anything else being done in Italy between the wars and exemplified the best work done in the “Rationalis.

Early influences

He was born on 2ndJune, 1906 in Venice. Scarpa spent his early childhood in Vicenza. After his mother’s death, at the age of 13 he, his father and brother moved back to Venice. Carlo attended the Academy of Fine Arts where, after two years, he focused on architectural studies. Graduating from a non-professional program, although he apprenticed with an architect, he was not permitted to practice architecture without associating with an architect. Hence, those who worked with him, his clients, associates, crafts persons, called him professore, rather than architetto.A vagabondage that opened his eyes

We can imagine the art of seeing, which Scarpa came to possess by the end of his apprenticeship, as the result of the intellectual vagabondage that characterized his education. He whiled away the time in gazing, portraying himself through drawing the objectivity of that which he observed. His peculiar formal culture derived from the eye, and by observation he mastered technique. For instance, when he was designing his glass objects in the ’30s, he was also observing contemporary figurative works. Other characteristic features of Scarpa’s culture confirm this attitude. For instance, he devoted himself to the study of the various techniques of construction, whether in glassware or museum design, in the use of materials or those involved in essential building skills. Hence, in his effort to break through a norm by introducing distortions and even flat contradictions into technical details and constructional solutions, one finds tangible evidence of his rejection of habits and the empty values of utility whose premise they are.First projects

In 1922-24, he began his first project as a collaborator in the office of Architect V. Rinaldo and in 1926 obtained his diploma of Professor in Architectural Drawing at the Royal Academy of Fine Art in Venice. He then began his career at the Royal Superior Institute of Architecture of Venice (subsequently Architectural Institute of Venice University) as assistant to Prof. G. Cirilli. He possessed an exceptional understanding of raw materials, and from 1933 to 1947, was artistic director of Venini, one of the most prominent producers of Venetian glass before he began the pursuit of his career as an architect.Scarpa’s revolutionary breakthrough style

Impact of his style

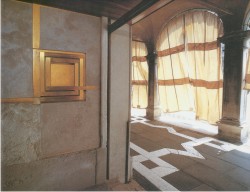

When he renovated the Galleria Querini Stampalia, a Venetian palazzo, he renewed the balance between structure and landscape by conceptualizing the building as a vessel that could contain the incoming tide within its foundations. Channels direct the water through the lower level of the palazzo, so that the building shapes the water. At the same time, the natural flux of the water shapes the building.Right from the start, when Scarpa preferred to study with the master glass workers of Murano rather than bow to the restrictions of academic culture, one finds him using drawing and execution as part of the development of experience. The work he achieved up to the start of the ’50s reveals the role of visual memory in Scarpa’s work. Here he fine-tuned his appreciation of materials and the design of small-scale objects. The combination of this sensitivity for tactile detail with the use of spatial effect links Scarpa’s architecture to the De Stijl movement and Frank Lloyd Wright, an important co-believer in making buildings appropriate to their surroundings.

Memorable projects

Architect of Cemetery, celebration of death The Brion-Vega Cementery, San Vito, Italy

One of Scarpa’s most famous projects is the Brion-Vega cemetery of San Vito, Italy, where he created a series of family tombs and a landscaped garden around them (1970-1972). Using modern forms and materials (principally concrete), Scarpa responds to traditional funerary architecture, yet provides a bridge into the future. The cemetery becomes a transitional place where the corporeal becomes ephemeral, and solids slip away into voids. In the cemetery garden, the earth is raised in monolithic trays and separated from precinct walls by a narrow space. Brick paths cut through the raised earth, and large, curved concrete forms act as bridges, wells, and walls. The tombs themselves are partly recessed in the ground, yet also raised off the ground like freestanding sarcophagi.

Creator of museums, history revisited Exhibit spaces of the Castelvecchio, Verona and Accademia and Correr Museum, Venice

Designer of gardens, paradise recreated Public sculpture gardens in Venice, Verons, San Vito di Altivole

The first public sculpture garden in Italy is designed for the Venice Biennale, and the gardens for the Fondazione Querini- Stampalia, the Museo di castelvecchio in Verona, and the Brion family Sanctuary in San Vito di Altivole. The gardens Scarpa designed evince a wide range of sources, from Persian paradise Gardens, the gardens of Classical China and Japan, and the Garden culture of Venice and the Veneto. The Venetian traditions that informed Scarpa’s work include the images of idealized landscapes produced by Venetian School of Renaissance painting and the techniques by which those paintings were produced. Scarpa’s design work was also located within tradition of architectural production in which architecture and landscape are understood in a degree rather than in kind. Scarpa’s work as a designer of landscapes and gardens was largely informed by his work as an exhibition designer.

Scarpa’s projects outside Italy

While most of his built work is located in the Veneto, he made designs of landscapes, gardens, and buildings, for other regions of Italy as well as Canada, the United States, Saudi Arabia, France and Switzerland. One of his last projects, left incomplete at the time of his death, was recently altered (October 2006) by his son Tobia—the Villa Palazzetto in Monselice. This work is one of Scarpa’s most ambitious landscape and garden projects, the Brion Sanctuary notwithstanding. It was executed for Aldo Businaro, the representative for Cassina who is responsible for Scarpa’s first trip to Japan. Aldo Businaro died in August 2006, a few months before the completion of the new stair at the Villa Palazzetto, built to commemorate Scarpa’s centenary.In 1978, while in Sendai, Japan, Scarpa died after falling down a flight of concrete stairs. He survived for ten days in hospital before succcumbing to the injuries of his fall. He is buried standing up, in the outside corner of his L-shaped Brion family cemetery at San Vito d’Altivole in the Veneto.

The champion of craft, materials and metaphor

Scarpa’s decorative style has become a model for architects wishing to revive craft and luscious materials in the contemporary manner. Carlo Scarpa was such a visionary; he created the monumental through the personal, allowing a sense of place to guide his designs and the construction of metaphor to have equal weight with the demands of functionality.